April 15, 1912 is a day that went down in infamy. On that chilly morning the luxury British passenger ship the Titanic sank after colliding with an iceberg on route from Southampton, England to New York City. The story of the Titanic is well known but what may be lesser known is that the prosperity of the hops industry in Lewis County also hinged on that incident, when Herman Klaber, the “King of Hops” went down with the ship.

It all began with the first “King of Hops” Ezra Meeker, who is famous also for retracing the Oregon Trail and leaving in his wake historic markers from Puyallup to Washington D.C. Meeker established hops farming in Western Washington in 1865 and started a wave of growers converting their wheat fields to the more lucrative hops. Meeker even published a book in 1883 to help Washington growers called, Hop Culture in the United States. But in 1892 a tiny mite ravaged Pacific Northwest hops and pushed Meeker out of the business.

A young man named Herman Klaber started in the hops business just before Ezra Meeker quit. In the early days Klaber started with William Uhlmann and Co. of San Francisco and New York, one of the nation’s largest hops dealers as a clerk but he quickly moved his way up to become a representative of the company around the nation negotiating the price of hops.

Klaber who was by many accounts a genial, optimistic and ambitious fellow, soon went into partnership with his cousin Marcus J. Netter and Max Wolf to form Klaber, Wolf & Netter, hops dealers. Their offices were in London, San Francisco, Tacoma and Portland.

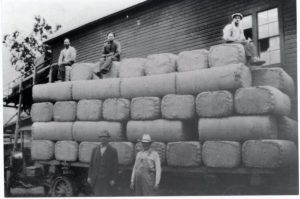

Klaber’s business as a broker grew but he was also interested in creating his own model hops farm, one that would be more than just a farm, but also a community. Throughout his travels he had seen many hops fields but he was particularly impressed with the hops coming out of Lewis County. According to the April 12, 2001 issue of the News Tribune, “In 1906, Klaber’s empire expanded to Lewis County. He bought 360 acres in the lush valley that locals called Baw Faw, for they thought that was how the French pronounced Boistfort. The name is French for ‘small valley surrounded by green hills.’”

Julia McDonald Zander writes in her book Herman Klaber: King of Hops, “Klabber invested $75,000 (equivalent to nearly $2 million today) to build a community that he initially thought of naming Klaberville but eventually called Klaber. Six towering chimneys on modern dry kilns spelled out the town’s name -KLABER- with one letter per chimney, visible for miles around.”

For himself, Klaber built a two-story house on a knoll overlooking the hops yard. For the town he built a general mercantile, a blacksmith shop, barber, post office and meeting hall. Around 1,000 pickers arrived each year in early September, many of whom were Chehalis and Cowlitz Indians. They lived in either tents or one of the 400 wooden shacks Klaber had built.

A picker could earn three dollars a day but one of the best aspects of being a picker was the opportunity to socialize. As Zander puts it, “Under sunny skies with warm weather, women and children often enjoyed the chance to visit and play while picking the cone-shaped hops from vines climbing twelve-foot high poles. Evening entertainment included music and dancing in barns on the farm.”

In 1907 Klaber married Gertrude G. Ginsberg daughter of a Russian born cigar store owner. Though they often traveled, Gertrude and Herman shared their Tacoma home and later a Portland home with extended family. The couple welcomed their daughter, Bernice Janet Klaber, on February 8, 1910. Every summer the family moved to their countryside home in Klaber.

In 1912 Herman Klaber left his family behind and sailed to Europe for a three-month long excursion seeking hops buyers. Interestingly, just before he left he met with his lawyer and signed his last will and testament. After checking in with his London office Klaber traveled around Europe drumming up business.

According to the Seattle Times, April 21, 1912 Klaber wrote a letter to business partner Ben Moyses, “I have determined to leave here for home on the new Steamship Titanic. The other day I was sitting in a leading hotel here and noticed a man reading what looked like an American Newspaper. I ‘rubbed’ over his shoulder and found that it was a copy of The Seattle Times. My, it looked good to me to see a Seattle newspaper here in London. I introduced myself and found that I was talking to Seattle business man, W. R. Owens, and we spent five hours talking about ‘God’s country.’ I hope to be there soon and I shall leave here as soon as I can make arrangements.”

Herman Klaber, aged 41, purchased ticket number 113028 which put him in room C-124 aboard the Titanic. The ship carried some 2,200 souls. It was around midnight that the unsinkable Titanic struck an iceberg. Some 705 passengers, men, women and children boarded lifeboats.

“Passengers lucky enough to board lifeboats,” wrote Zander, “saw men lighting cigarettes and waving goodbye, musicians performing on the deck and crewmembers scrambling to load the last lifeboats.”

Herman Klaber’s body was never recovered and he was listed as one of the wealthiest to perish.

Though the Klaber hop yard continued for two more decades, the business floundered. A powdery mildew plagued the harvests, World War I interfered with shipping to European customers and prohibition restricted the American market. The ever optimistic Klaber may have seen the hop yard through these travails but without his strong leadership the business declined. In 1945 the hop yard closed and the community of Klaber faded away with it.

For continued reading:

https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-victim/herman-klaber.html

https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/king-hops-legacy-herman-klaber.html

Herman Klaber: King of Hops by Julia McDonald Zander

Herman Klaber on geni.com